Thank you for joining us virtually on Wednesday, September 20th, 2023 from 12:00 pm – 3:30 pm (PST), for “We Welcome The Children Back Home: The Burden of Sorrow and Survival of the Indian Residential School Experience in Canada.” This Indigenous Speaker Series session brought together a panel of survivors of the Indian Residential School experience in Canada. This important session welcomed and honored these brave and resilient survivors as they lead us in a discussion about the urgency and motivation to right and write a new history in Canada that is based on a proper redress for Indigenous peoples and communities. We Welcome the Children Back Home is an expression to acknowledge those survivors in Indigenous families and communities who are hurt and hurting, and who are simultaneously coming to terms with the past and finding a way forward.

This virtual event is presented by the Indigenous Speakers Series.

Panelists

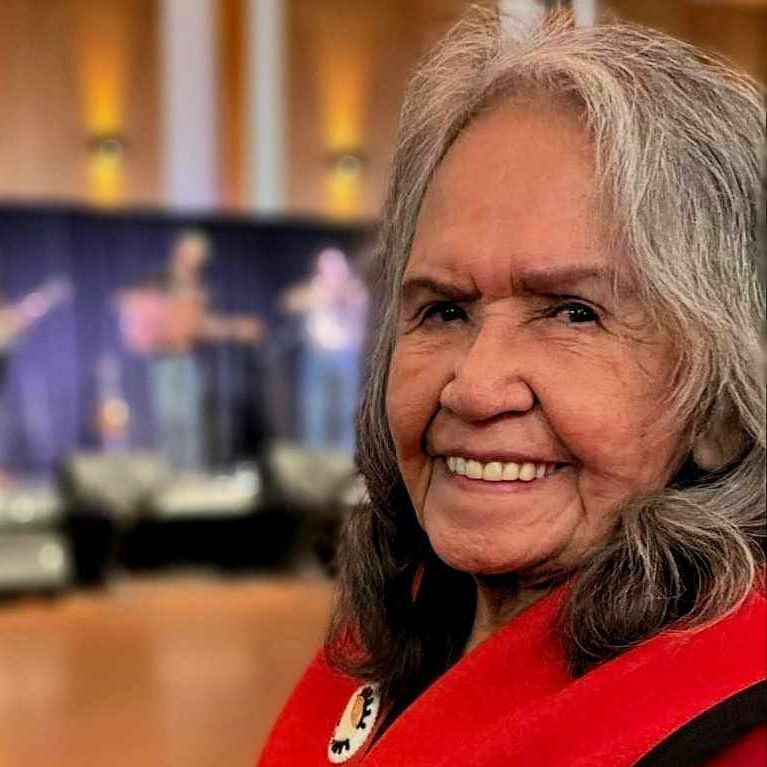

Constance Humchitt – Thalth Gwaith

My everyday name is Constance Pearl Humchitt-Tallio and my traditional name is Thalth Gwaith which means Copper Woman, and to many friends and family I have been known as Connie – the name I will use during this presentation.

My parents were Hereditary Chief Wigvi ba Wakas – Chief Eagle Nose, Leslie Humchitt and Umaqs – Emma Humchitt of the Heiltsuk Nation. I am the third child of two brothers and three sisters. My younger brother now holds the Hereditary Chieftainship that my great-grandfather held since the 1800s.

The beginning of my educational journey began in 1950/51 in grade one at our Indian Day School in Bella Bella, and thereafter to the Boarding Home Program since they did not have grade 8, and so we had to leave to progress into Junior High and then again onto to the [Port] Alberni Indian Residential School from 1957 to 1960.

I am currently a Native Language Teacher in my Community of Bella Bella and I teach Kindergarten students aged 4, 5 and 6 years. I have a Language Proficiency Certificate with SFU, for which I can teach under the Ministry of Education, and I am also a Curriculum Resource Coordinator with the Bella Bella Community School. I was a Grandfathered in Social Worker and employed with my Band.

My volunteer time is researching family history, family trees, and anything to do with assisting families in this way. I am a Commissioner for the Province of BC on behalf of the Heiltsuk Nation, a Representative for our Mynuyags – Women’s Council on Joint Leadership for the Band, Treasurer for our Church, and I am active in numerous other entities.

Fran Tate

My name is Frances Anne Tate (nee Robinson), and I was born on July 5th, 1943, to Mac Robinson and Mary Edgar at Dodgers Cove near Bamfield, BC. I was only a young adult when my parents passed away.

I was taken from my parents at the age of 7 years and brought to the Alberni Indian Residential School.

My traditional way of life ended the day I arrived there, and I remained there until I was 16 years. During my time there I participated in some sports such as basketball, softball and participated in choir. During winter holiday school breaks I was unable to travel to my home community because of severe weather conditions, and my father’s only means of transportation was a dugout canoe with a small outboard motor, and I was billeted out around Port Alberni to homes that would take me in for a few weeks during this time.

During summer holidays around the time I was 13 until I was 16, my parents picked us up to go berry picking in the United States, and one location I recall was Vascas Island. Picking berries was our way of making money to support our parents at that time.

My participation with the Language Department at our new community school began when Adam Werle began teaching the Language class. In 2007 I began to read and write our Ditidaht Language, and shortly after I was hired as a language teacher to teach in our school. I did this from 2008 until 2019 when COVID-19 hit our community and the school was closed. Also, our language staff taught the toddlers at our Aasuubus Daycare.

I was asked to mentor 2 daycare staff as they enrolled in the language emersion program to benefit teaching the children during their time at daycare. I also participated with building up our language platform that is on the First Voices website. The elders in the community all contributed to adding words and phrases on this valuable site.

In closing I am proud of my family I have built with my late husband David Tate. We had eight children together, and we have 34 grandchildren and 18 great grandchildren.

Frances P Tait

Fran was born in Lax Kw’alaams – Port Simpson, BC and she currently lives in Nanaimo on Vancouver Island. Along with her two brothers, Melford Tait and Andrew (Woody) Tait, she was sent to the Alberni Indian Residential School (AIRS) from 1951-1966 from the ages of 5-18 years. She graduated in 1966 from the Alberni District Secondary School. After being sent to AIRS she did not go home until she was 12 years, and she spent 1958-59 in the Port Simpson Day School. At the age of 15 years she was sent to Metlakatla, Alaska to attend school from September through to December before she was sent back to Prince Rupert. She then was asked to be sent back to AIRS for grades 11 and 12 because she knew the school better than she did her home community, and she knew where she would fit in, in the scheme of things and her life. Fran completed Grade 13 at West Vancouver High School in the Department of Indian Affairs home-school program. She attended UBC in 1971- 1972 but did not complete the BA program, and she has no interest to do so now. She was employed by the Malaspina College (Malaspina University College) as an Academic Advisor from 1974 to 2006, when she retired. She is an Elder in the Vancouver Island University Masters’ of Education program. In her retirement she’s an avid Dragon Boat paddler. Fran is actively involved as a Survivor in an advisory capacity with the AIRS Research Team with the Tseshaht First Nation. She also is a supporter of the Alberni Indian Residential School Survivors Art & Education Society.

Margaret Commodore

Margaret Commodore (aka Margaret Joe) is of Stó:lō ancestry, and she was born in 1932 to Andy and Theresa (nee Prest) Commodore in Chilliwack, BC. She spent the early years of her life at Deep Bay where she attended public school in 1938, then Coqualeetza Indian residential school in 1939. By 1940, Margaret, along with her siblings, were sent to the Alberni Indian Residential School. In 1947, at just 15 years, she left Indian residential school and moved back to the Fraser Valley where she held numerous jobs including gas jockey, and as a fruit and hops picker. From 1948 to 1965, Margaret worked on and off at the Coqualeetza Indian/TB hospital.

Margaret lost her Indian Status in 1957 when she married a whiteman. From this marriage she had two daughters, Jacalyn Mae and Tracy Leigh. Being a non-Status Indian brought many challenges in her young life – for one she was not allowed to return home to live on her reserve of Soowahlie. Her strong will never ceased to fail her and she went on to Vancouver Community College where she earned her Practical Nurse Certificate. In 1965, she obtained a job in Whitehorse, Yukon, and by this time she was a single mother, and so she packed some personal belongings and along with her two young daughters they began a new adventure in Northern Canada. In 1966 she married her second husband and had another daughter, Sheila Ann. She took a few months off of work to be a stay-at-home mother but her yearning for a better life for herself and her young daughters brought her to the next journey in life – politics. Her political career began in 1971 when she was elected as Vice President of the Yukon Association of Non-Status Indians (YANSI). The injustices and discriminations she faced over the years brought out the fierce side of her. For many years she worked towards helping Non-Status Indians and Women to obtain equality in the ever-dominant white male society.

Margaret was also a Justice of the Peace for a few years before she decided to get back to politics. In 1982, she was elected as a Member of the Yukon Legislative Assembly (MLA) for Whitehorse North Centre and subsequently re-elected in the years 1985, 1989 and 1992. Margaret was the first Aboriginal Minister of Justice in Canada, but in previous years she was named to Minister of Health and Human Resources, Women’s Directorate, and the Yukon Liquor Corporation. She finished a successful and accomplished political career when she retired in 1996. However, during this span of her career it was not without a setback which triggered her memory. It began when Margaret went to a local art show by an accomplished artist, Jim Logan. The pictures depicted scenes of Indian residential school life. The painted images brought back vivid memories – memories she kept buried for decades. It was at that moment the horrific abuse she suffered in Indian residential school came back like a dam bursting. She returned to her office and cried for hours.Shortly after, Margaret heard her homelands calling her back to her birthplace and she returned to Chilliwack in 1996. However, the haunting memories of Indian residential school remained. She decided it was time to start talking and begin her healing journey. She attended the trauma program, not once but three times, at the Tsow-Tun-Le-Lum Treatment Centre in Nanaimo, and she believes that “You can’t just go there once and expect the pain to leave. You have to do it more than once…when you carry the pain as long as I did, it’s harder to get rid of it.” In 2013, she finally told her story in front of thousands of people at the Truth and Reconciliation Commission gathering in Vancouver, BC. It was the first time two of her daughters heard her heartbreaking story. During her testimony she said, “I won’t apologize for my tears. I deserve them….my healing will last for the rest of my life.”

Charlie E Thompson – Buukwilla

I am Charlie Elwood Thompson – Buukwilla and I am from the Tsuubaas First Nations, formerly of the Ditidaht First Nation. I have lineage in Nuuchahnulth and Coast Salish.

I was born July 6, 1946, in the state of Washington where my late mother was berry-picking like many First Nations people did back then. I was born in a small shack in a strawberry field.

In 1955, at the age of nine I was brought to the Alberni Indian Residential School (AIRS), along with my two younger brothers – Jack and Arthur. We all spent ten years in that institution not knowing why we were brought there. During those years I lost my language and most importantly my culture. I had no opportunity to know who I really was, and I became an assimilated Indian and left knowing that because I was told the old ways were wrong and I believed it.

A lot changed when Survivors started finally talking about what happened to them, and for a while I was too afraid to speak about my time at AIRS. The turning point for me was when a group of boys took Arthur Henry Plint, a dorm supervisor at AIRS, to criminal court and we won. He was sentenced to eleven years in prison. This action allowed me to talk and start a criminal action to the supervisor who abused me, my brother and a friend. Unfortunately, the supervisor passed away before the court date.

After a few years of doing my best to deal with what happened to me at AIRS I eventually got to a place of being okay. I enrolled in a counselling course at Malaspina College along with other Nuuchahnulth people, and although I struggled in that course I made it through with a certificate. This gave me an opportunity to work with our people who were traumatized at Indian Residential Schools. I enjoyed helping Survivors.

I have seen our community divided so bad that there seems to be an impossibility to get past it or deal with the issues that keep us apart. But, I have hope that the next generation can deal with it and move onto a better future.

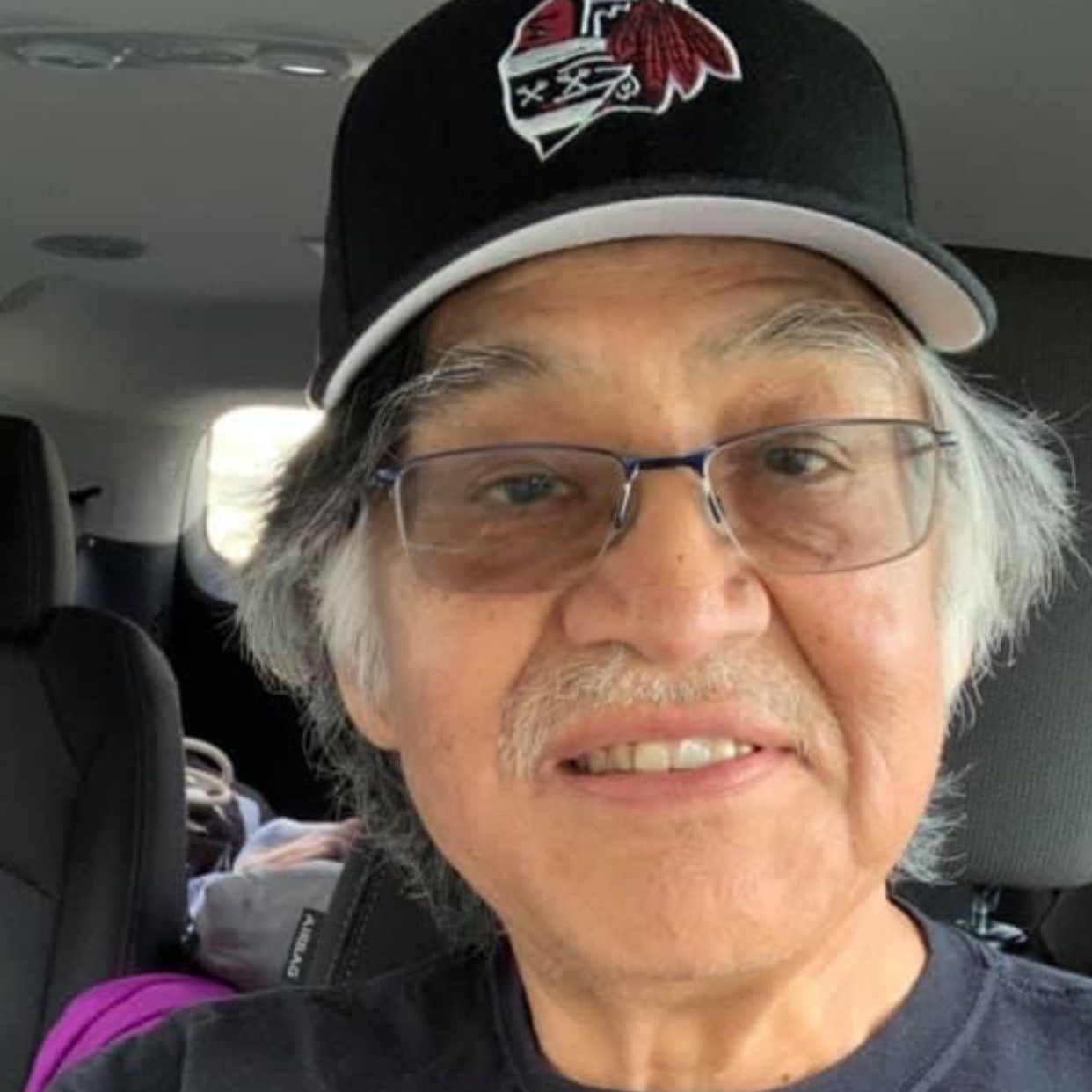

George Jack Thompson

George Jackie Thompson was born in Tacoma, Washington on July 31, 1947. I lived my young life in the village of Whyac where we used to play on the beaches all day until it started getting dark. Our mother, Ida Thompson (nee Modeste), used to tell us to get home before it got dark, and we also would visit our great-grandparents Nookwa and Tuxbeek in Clo-oose, and they would feed us when we got hungry. At times we would stay in Duncan with our Grandparents, Elwood and Mabel (nee Good) Modeste, my mother’s parents.

Sadly, we went to the Alberni Indian Residential School in 1955. Our mother wanted us to go to school in Duncan, and in fact already had us registered but our father said we are going to Alberni Indian Residential School, and he said, “So they can make men out of them.” We never had the opportunity to ask him what he meant because he passed away at a young age.

In 1967 I married Nona Margaret Williams and we have 4 beautiful children – Iris, Wendy, Jack, and Colleen, and later on we adopted Barry Patrick our youngest son. In the same year I started learning about our culture and learning to dance from my grandfather George Thompson.

I went to Vocational School in Nanaimo at Malaspina College and took up a Welding Course. After completing the course, I started welding in a Logging Camp at Nimpkish earning $50.00/hr. I moved around to different Logging Camps and finally ended up in Narrows Inlet, Sechelt. In all I welded for 18 years. And crazy me got into Politics with the encouragement of my Uncle Stan, and I was the elected Chief of Ditidaht First Nation for over 20 consecutive years.

Robert Daniels, BA, MA

I am an Indian residential school survivor. Indian residential school was a horrendous experience where I suffered physical, sexual and mental abuse at Alberni Indian Residential School (AIRS). My kindergarten year was at the First United Church at Koksilah, BC and it was a good experience there. I spent twelve years at the Alberni Indian Residential School, from 1950 to 1962. My Indian residential school experiences spawned within me deep feelings of hurt and anger that I still carry today. These feelings of hurt and anger do not drive my life today, but they still exist, pushed deep down in my self-consciousness. These feelings come to me as I listen to other residential school survivor’s stories.

After twelve years at AIRS, when I returned home, people in my community did not know who I was, except for my family. This Indian residential school education and experience is significant with me having to heal after returning home and with an empty soul, without knowing any of my own culture and traditional language. After years of hard lessons in life, I found balance through my culture, Elders teachings, and with personal counselors. Our cultural heritage plays an important healing avenue as my family’s inheritances and customary property carries so much rich family history. Yet my culture and traditional language was forbidden at AIRS, and we were punished anytime we spoke our traditional language and I was not taught my own culture.

I learned through my tough life lessons and my bad experiences. I did not have any critical and creative thought processes. I was never taught or even allowed to take a position or defend it. Our Indian residential school environment was very strict and regimented. We lined up and marched into the dining room, marched into the auditorium for morning religious services – twice on Sundays. I was slapped in the face so hard by the infamous supervisor, Arthur Henry Plint, because I did not snap to attention.

My Indian residential school experiences included religious indoctrination enforced by corporal punishment and myriad forms of abuse, cultural and bodily shame, alienation from my family, and a disconnection from subsistence economies. Once we were self-sufficient and living without any government assistance, and our pantries were always full of jarred and canned salmon and fruit that brought us through the winter.

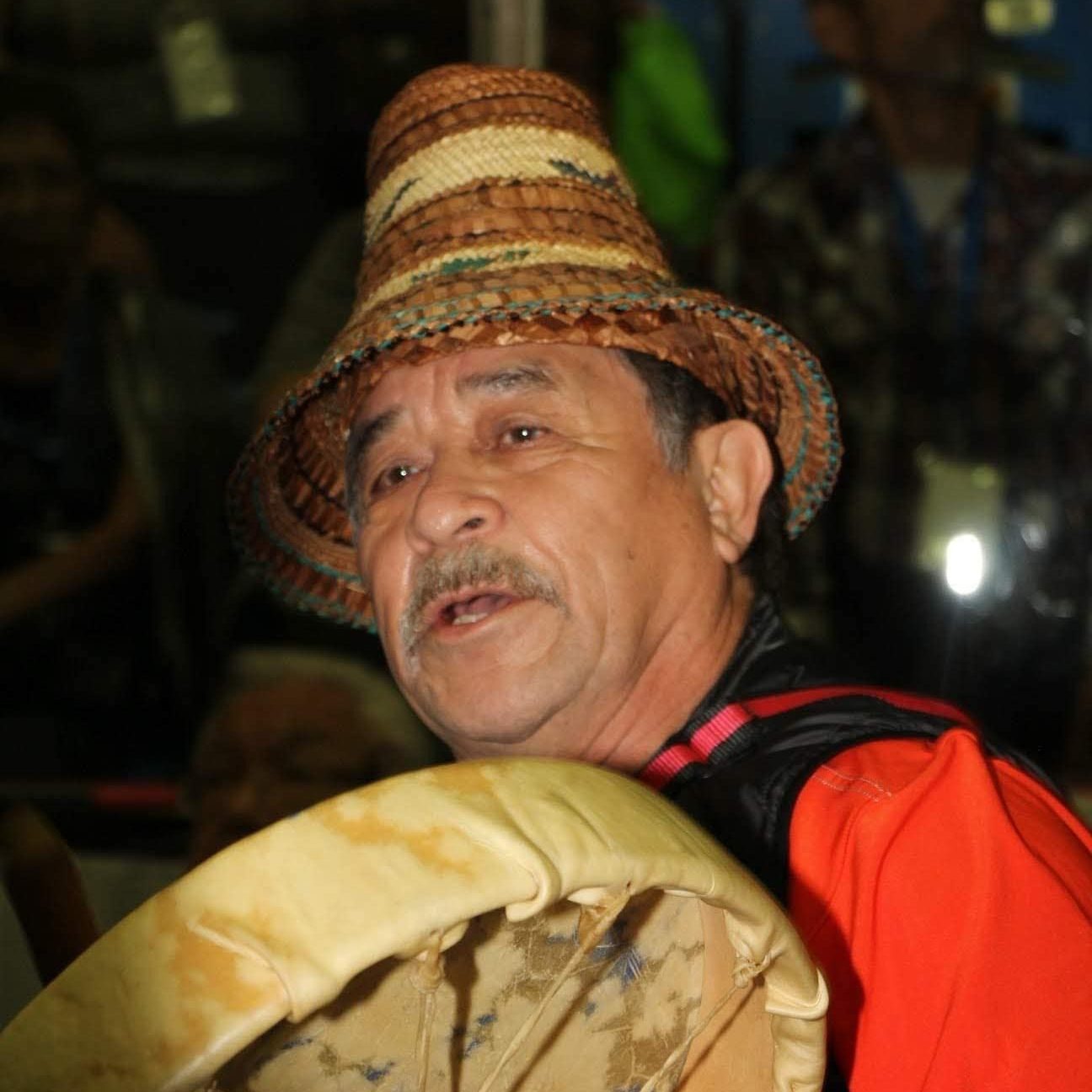

Wally Samuel

Wally was born and raised in the Nuuchahnulth village of Ahousaht. His late father was Daniel Samuel of Ahousaht and he was a commercial fisherman and trolled the west coast of Vancouver Island from Tofino to Kyuquot, where Wally liked to spend most of his summers. His late mother, Hazel Olebar, was from Kyuquot. Wally was born in a time where he observed the Ahousaht language, culture and traditions being practiced. The highlight of his childrearing was listening to stories from the Ahousaht people and Elders who were a part of the rich history and traditions of Ahousaht as it was in the 1800s.

Wally has 35 years of public service, managing, planning and implementing community programs, activities and services. He understands the Ahousaht dialect and can speak some, and he leads the Ahousaht Cultural Group in Port Alberni for the teaching and preservation of Ahousaht songs and dances. Wally knows, respects and practices First Nations culture and protocols. He has also given presentations on Indigenous tourism and First Nations partnerships across BC and Canada, as well as in Australia.

Wally is a Survivor of the Alberni Indian Residential School, and he has done presentations at schools, libraries and public events on his perspectives of the Indian residential school experience.

Support

Shane Pointe | Ti-te-in

Cultural Support

Ti-te-in | Sound of Thunder – Shane Pointe is a Musqueam Knowledge Keeper, and his motto is Nutsamaht! – We are one. Ti-te-in is a proud member of the Salish Nation, the Pointe family, and the Musqueam Indian Band. In addition to being a proud grandfather and a great-grandfather, he is a facilitator, advisor, traditional speaker, and artist. Shane has worked for five different school boards, Corrections Canada, Simon Fraser University, The University of British Columbia, and the First Nations Health Authority. He provides advice and guidance on ceremonial protocols for local, national and international cultural events.

Cynthia Jamieson

Mental Health and Wellness Support

I have been providing counselling and supervision of counselling services for over 15 years for couples, adults, children and youth. I have a Master of Social Work Degree and I am also a Certified Life Coach. My areas of specialty include trauma, couples counselling, youth, addictions, depression/anxiety, grief, OCD, crisis counselling, work/life balance and eating disorders. Therapeutic modalities that I incorporate into my practice are Cognitive Behavioural Therapy, Dialectical Behavioural Therapy, Emotionally Focussed Therapy and Structural Family Therapy.

I am an Indigenous person of mixed ancestry with an Indigenous father and a Caucasian mother. Originally from Six Nations of the Grand River in Ontario, I have worked with several First Nations communities in BC, including Tla’Amin, Mowachat, Cowichan, as well as urban and Metis populations.

Moderator

Derek K Thompson – Thlaapkiituup, Director, Indigenous Engagement

Description

Written by Derek K Thompson – Thlaapkiituup, Director, Indigenous Engagement

Think of where you were on June 11th, 2008.

There have been many descriptions about the Indian residential school experience in Canada that maintain Indigenous – First Nations, Inuit, Métis – peoples lost their language, lost their identity, lost their culture, that children lost their innocence. We didn’t lose anything. Our individual and collective purpose to sustain who we are and where we come from was stolen. Beautiful and bright children were completely dispossessed of everything and anything resembling their own language, their own identity, their own culture, and their own innocence. Robbed of all that is good and wholesome, robbed of anything resembling the people they come from, robbed of the surety of confidence and innocence. This history that stole our children, and who are children no more.

Be mindful of what you’ve done since September 30th, 2022, and September 30th, 2023.

On September 21st, 2022, in a solemn effort to acknowledge the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation we brought together a panel of people who are children of Indian residential school survivors. The conversations on that day inspired a shared desire to stand together in love and support for these brave speakers whom endured the legacy of abuse, hurt, trauma, and grief. The day was filled with sorrow and uncertainty, and it was also overflowing with forgiveness, understanding and confidence.

On September 20th, 2023, we are bringing together a panel of survivors of the Indian Residential School experience in Canada. This important session will welcome and honor these brave and resilient survivors to lead us in a discussion about the urgency and motivation to right and write a new history in Canada that is based on a proper redress for Indigenous peoples and communities. We Welcome the Children Back Home is an expression to acknowledge those survivors in our families and communities who are hurt and hurting, and who are simultaneously coming to terms with the past and finding a way forward.

Think about what you will do between September 30th, 2023, and September 30th, 2024.

September 30th, 2023, will mark the 3rd annual National Day for Truth and Reconciliation. This important day is an opportunity for all Canadians and British Columbians to think about the continuing legacy of the Indian residential school experience in Canada as well as the broader impact of colonialism, oppression, assimilation, and racism against Indigenous – First Nations, Inuit and Métis – peoples. It’s a chance to enrich our individual and collective understanding of the past and to create a new chapter in our shared history that is founded on the principles of respect, truth, reconciliation, and redress.

June 11th, 2008, marked the formal statement of apology to former students of the Indian Residential School Experience in Canada made by the Prime Minister in the House of Commons on behalf of all Canadians. We’ve known before and since this apology that this horrific experience also includes those children that never made it home, that we’re buried at former sites of Indian Residential Schools, and that never got to experience the acknowledgment of an apology nor the comfort of being able to come to terms with their past, with their family, with their community.

Topic: We Welcome The Children Back Home: The Burden of Sorrow and Survival of the Indian Residential School Experience in Canada

Date: Wednesday, September 20th, 2023

Time: 12:00 – 3:30 pm (PST)

What Will I Learn?

You will learn about the context of truth, reconciliation and redress from survivors of the Indian Residential School Experience in Canada.

Continue Learning

“The time to make things happen is now. The time to seek out our individual and shared power is now.”

Learn more about REDI’s Indigenous Initiatives here

Discover more about REDI’s Indigenous Initiatives Speakers Series here

Find REDI’s Indigenous-Specific Resources here